I’ve always found the term “mincemeat” to be pretty confusing. It has meat in the name, but this tiny pie I’m eating is sweet and fruity. What is going on here? WHAT IS MINCEMEAT PIE!? WHAT IS MY PURPOSE IN LIFE!?!?!?!?

Ahem.

Mincemeat was once meat. The pie had several different names; mincemeat pie, mince pie, Christmas pie, shred pie, shrid pie, or minched pie. It was still sweet, but also savory. Sweet and savory, kind of like sweet and sour chicken. Only not bad American Chinese food, even if it causes just as much indigestion.

The actual mincemeat (not the whole pie) today is a spicy preserve made of dried fruit, apple, beef suet (the hard fat around the cows kidneys), candied citrus peel, and spices. Occasionally the mixture is steeped in rum, brandy, or Madeira and has the honor of being the traditional filling for those tiny Christmas pies you see in stores. Mincemeat can also be stored in jars like jam and used in other hot desserts, such as mincemeat omelets flavored with brandy, steamed suet or sponge puddings, and baked apples. I dunno about you, but steamed suet sounds awesome to me. But for clarification purposes, steamed suet pudding is any pudding encased in a crust made with suet.

The act of “mincing” something means chopping it up into itty-bitty baby pieces. It’s kind of like making a hash, example: corn beef hash. The saying “to make mincemeat of someone” first appeared in the 17th century and was spawned from the act of mincing. I found two different Latin origins of the word “mince.” One is minuere, “to diminish,” and the other is minutia, meaning smallness. “Pie” originates from the word pica, Latin for “magpie,” because the hodgepodge of ingredients in a pie resembles the randomly collected objects of a magpie. I love the word hodgepodge.

The filling for the mincemeat was a way to utilize leftover meat, stretch protein, and allow meat to be in other dishes besides the main one (like pies). These practices were most common from the Middle Ages until the Renaissance. An essayist from The Gentleman’s Magazine in December 1733 says that “minc’d” pie was popular around Christmastime because of the barrenness of the season and the lack of fresh fruit and milk to make tarts, custards, and other desserts. It was a way to have dessert on Christmas without having a traditional dessert.

Originally mincemeat simply meant, “minced meat,” but the meaning changed around the 16th century. In the Middle Ages up until the mid-19th century, they were called Christmas, shred, or minced pyes. One source I used claims that around the time of Queen Elizabeth I or James I, the pies were called “minched pies” and yet another says they were popular under the name “mutton-pie” as early as 1596. The name changed when the mutton in the pie was replaced with neat’s (calf’s) tongue. Honestly, I couldn’t find out exactly what it was called when, so I’m going to call it mince pie or Christmas pie for my own sanity. The distinction between “mincemeat” and “mince” began appearing in written records and cookbooks around 1850 when “mince” was being used to describe minced meat.

Mince pies originated in England right after the crusades. Knights returning from their travels brought back interesting Eastern spices and new cooking techniques. It became popular to mix sweet and savory tastes and many recipes for meats cooked with fruit and sweet spices appeared. The earliest type of mince pie was a small medieval pastry called the chewette. The chewette contained chopped liver, or fish on fast days, mixed with chopped hard-boiled egg and ginger, then baked or fried. Eventually it was enriched with dried fruit and other sweet ingredients and became mincemeat.

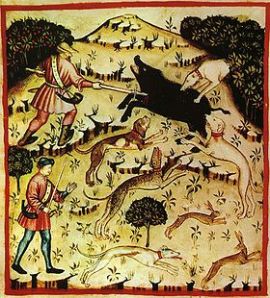

In the Middle Ages, fruit was added to the pie as a preservative, the most common being raisins, apples, and currants. Other ingredients included the new Eastern spices, meat from several game birds and other game animals, sugar, suet, and molasses (possibly even black treacle). Mincemeat pies were bigger then. The largest recorded pie in the Middle Ages was about 9 feet in diameter and weighed around 165 pounds. It contained two bushels of flour (which could be anywhere from 84-120 pounds of flour depending on the type of flour), 20 pounds of butter, four geese, two rabbits, four ducks, two woodcocks, six snipes (type of bird), four partridges, two cow tongues, two curlews (type of bird), six pigeons, and seven blackbirds.

A fairly accurate picture of a feast. Also, one of my favorite books. I showed an appreciation for food at an early age.

A recipe from 1394 calls for one pheasant, one hare, one capon, two pigeons, two rabbits, all butchered with the meat separated from the bone and minced into a hash. Then the livers and hearts of all the animals were added, as well as two sheep’s kidneys, small meatballs of beef, eggs, pickled mushrooms, salt, pepper, vinegar, and spices. They were cooked in the same broth the bones were cooked in, poured into a piecrust, and baked. In 1721, goose was one of the main ingredients in Christmas pies of northern England. A recipe from 1822 includes beef, suet, sugar, currants, raisins, lemons, spices, orange peel, goose, tongue, fowl, and eggs. A 19th century Sussex recipe adds apples and brandy.

And then there’s this recipe from the Middle Ages:

“Mince and mix beef, suet of mutton, salt and pepper. Make a faire large cofyn, and put in some of this meat. Then take capons, hennes, mallardes, connynges …wodecokkes, teles, grete birddes and plom hem in a boiling potte; and then couch al this fowl in the coffyn. Add more of the meat and mutton as well as marrow, hard egg yolks, dates, raisins, prunes, cloves, mace, cinnamon, and saffron. Close the pie with a top crust and bake…but be ware, or thou close it, that there come no saffron nygh the brinkes therof, for then hit wol never close” (Cosman, p.60).

A pie spiced with saffron would take on some of its golden color and made the pie more theatrical. It was a necessary treat at a court banquet or party. There are a lot of recipes. I’m also starting a new band called Grete Birddes.

In the 16th century, “shred” or “shrid” pies were a Christmas specialty. They were called “shred” pies because the meat was shredded. The pie was usually served at the beginning of the meal, but once it changed to a more or less meatless pie it was served at the end of the meal as a dessert. The change to the pie we know now, sweeter and with little to no meat, was slow. In the 17th century the beef was sometimes partially or completely replaced by suet and in the 19th century meat has disappeared from both American and British pies. Except for the suet. Because everyone needs a little beef kidney fat in their lives.

Before the late 17th century, the Christmas pie had some religious meaning. The pie was made in an oblong shape to represent Christ’s crib in the manger and the top crust often had a pastry figure of the Christ child on the top. Sometimes the top crust was replaced with a lattice to represent the hayrack of the manger Jesus was born in. The spices in it, specifically cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg, were symbolic of the three gifts given by the Magi. It was also common for the pie to have 13 ingredients to represent Christ and his apostles, as well as some chopped mutton in remembrance of the shepherds. There is, however, some speculation that the pie was not originally baked in an oblong shape. In early recipes, the mince was described as being baked in “coffins” or “coffyns.” In the Middle Ages, the word “coffin” meant basket or box.

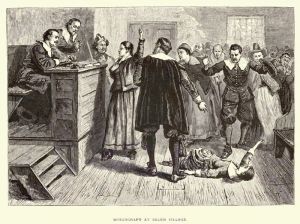

Either way, the pie infuriated the Puritans.

Let’s be honest, what didn’t infuriate the Puritans?

In any case, the Puritans believed the pies were superstitious, idolatrous abominations and Popish (offensive and “of or relating to the popes or the Roman Catholic Church”). The pastry baby was “idolatry in crust” form. The pie, and Christmas in general, was so offensive that Oliver Cromwell (that daffy guy who overthrew the English monarchy and created the Commonwealth of England, conquered Ireland and Scotland, and made himself Lord Protector until he died in 1658) banned Christmas and forbade the eating of Christmas pies. Chaplains of noblemen in particular, and clergy in general, were debarred because they enjoyed Christmas pies.

"Oliver Cromwell" by Samuel Cooper. I bet if he smiled more often he woulda been waaaay more into Christmas pie.

People continued making their pies anyway, but housewives decided to bake them in a round shape that had no apparent religious implications. That way no one could tattle on them. What were tattlers gonna do? Yell “YOUR PIE IS ROUND AND AN ABOMINATION!” and throw them in jail? I’m pretty sure that wouldn’t fly.

It wouldn't fly. Just like these penguins. Whose lives were narrated by Morgan Freeman. I'm so jealous.

Robert Fletcher wrote a poem called “Christmas Day” in 1656 describing the Puritans feelings about Christmas and its sinful treats:

Christ-mass? give me my beads; the word implies

A plot, by its ingredients, beef and pyes.

The cloyster’d steaks with salt and pepper lye

Like nunnes with patches in a monastrie.

Prophaneuess in a conclave? Nay, much more,

Idolatrie in crust! Babylon’s whore

Rak’d from the grave, bak’d by hanches, then

Serv’d up in coffins to unholy menl

Defil’d ith superstitiou, like the Gentiles

Of olf, that worship’d onions, roots, and lentiles!”

Dr. Samuel Johnson observed in his book His Life of Butler, published in 1835, that “We have never witnessed of animosities excited by the use of minced pies and plum-porridge, nor seen with what abhorrence those who could eat them at all other times of the year would shrink from them in December.” (Brand, p. 530). I have several more quotes, but I’ll tack them on at the end so you can have the option of reading them. But I encourage you to. They’re lovely. What you should take away from them is that in 19th century books that cover the topic of Christmas pies, there’s a lot about their banishment from the plates of United Kingdomers. I just made that word up.

After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 and Charles II became king, he reinstated Christmas and the tradition of eating Christmas pies returned. By this time they had switched from the savory pies of yore and morphed into round, baby Jesusless sweet desserts. I made that word up too. John Bunyan, author of The Pilgrim’s Progress, was a Puritan sympathizer and refused to eat mince pie when he was in jail in 1658 and 1660 and those other times. That guy got arrested like alllllll the time.

Multiple 19th century sources claim that the Quakers found it equally offensive. One writer was quoted as saying that Christmas pies were “an invention of the scarlet whore of Babylon, a hodgepodge of superstition, Popery, the devil, and all its works” (Brand, p.529). Whoa there, sparky. Take a breath and enjoy the crusty delight that is pastry baby Jesus.

In Victorian times, mince pies were good luck. Anyone who ate a mince pie on each of the twelve days of Christmas would have happiness for the next twelve months. The catch was that they had to be eaten in different houses each night and offered by a friend. The pies were usually cooked in dozens to strengthen the luck and it was considered extremely unlucky to refuse a pie. There was also the custom of making a wish when taking the first bite of your first mince pie of the Christmas season.

The pies were a type of hospitality. In the town of Piddlehinton, Dorset, the rector gave a pound of bread, mince pies, and Christmas ale to the poor visiting the farmers on December 21st, St Thomas’s Day (the traditional day for giving out charities and doles). Still, people were loathe to lose their pies involuntarily and often sat someone down to guard the pies the night before Christmas, which the ubiquitous Robert Herrick tells us about in one of his many Christmas themed poems:

“Come guard the Christmas-pie,

That the thief, though ne’er so sly,

With his flesh-hooks don’t come night,

To catch it,

From him, who all alone sits there,

Having his eyes still in his ear,

And a deal of nightly fear,

To watch it.”

That guy has like a bajillionty poems about Christmas.

There are plenty of literary references to mince pies as well. In Masque of Christmas, a play by Ben Jonson published in 1616, one of the characters is called “Minced-Pye.” She is dressed “like a fine Cookes Wife, drest neat.” In The Owl and the Pussycat, written by Edward Lear and published in 1871 and pretty much my favorite poem of all time, the Owl and the Pussycat “dined on mince, and slices of quince / Which they ate with a runcible spoon” after their marriage. Edward Lear just made up that word. In 1871.

And then there’s little Jack Horner. Ya know, that guy who sat in a corner eating his Christmas pie? Well, I heard he put in his thumb and pulled out a plum and announced to no one in particular “What a good boy am I.” A little too pleased with himself, if you ask me.

This little rhyme may actually be loosely based on fact. In the 1530’s, a young man named Thomas Horner worked as a steward to Richard Whiting, the last Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Abbot sent Thomas to Henry VIII with a large Christmas pie as a gift. However, instead of mincemeat under the crust, there were title deeds to 12 of the monastery’s best estates. The Abbot thought that by presenting them to Henry VIII, he would give Glastonbury a pass and not tear it down. Thomas figured out the deeds were in the pie, opened it, and stole one or more from it, including one for the Mells estate. The gift of deed-title-pie didn’t work (it was Henry VIII, what was the Abbot expecting?) and Whiting was hung in 1539 for treason. Horner went to live at Mells and Henry added Glastonbury to his collection of land. The plum in the poem represents the deed Thomas stole.

Mince pies were also a favorite in America, but they were eaten year round instead of at Christmas, so I won’t go into detail. After all, this is a Christmas post, but you should know this: mince pies were considered the American pie. Apple pie wasn’t a big deal until the 1940’s. Despite it’s popularity, the pie was believed by haters and lovers alike to cause indigestion, nightmares, disordered thinking, hallucinations, and occasionally death. The eating of mince pie was used to justify a man murdering his wife and also blamed for the death of George Humphreys, who died at sea because he ate too much mince pie. Not spoiled mince pie. Just too much of it.

High five, America.

Today, mincemeat pies are popular Christmas desserts in England, Canada, and other commonwealth countries. I know I mentioned it earlier, but it’s been a while, so I’ll repeat this part. They’re small, round pies, filled with a mix of dried fruits (raisins, sultanas, currants), chopped nuts, apples, molasses, sugar, suet, spices, and lemon juice, vinegar, or brandy. The pies you get in North America tend to be larger and feed several people. Many are baked with pastry stars on top, rather than a top crust.

Here I’ll share the quotes. They are about the Puritans and their extreme fear of Christmas pie.

“All plums the prophet’s son deny,

And spice-broths are too hot;

Treason’s in a December-pie

And death within the pot.”

-General Needham, History of the Rebellion (spice broth meant plum pudding, which was also banned)

“The high-shoe lords of Cromwell’s making

Were not for dainties – roasting, baking;

The chiefest food they found most good in,

Was rusty bacon and bag-pudding;

Plum-broth was popish, and mince-pie —

O that was flat idolatry!”

-Anonymous

“The Christmas-pie is, in its own nature, a kind of consecrated cake, and a badge of distinction; and yet it is often forbidden, the Druid of the family. Strange that a sirloin of beef, whether boiled or roasted, when entire is exposed to the utmost depredations and invasions; but if minced into small pieces, and tossed up with plumbs and sugar, it changes its property, and forsooth is meat for his master.”

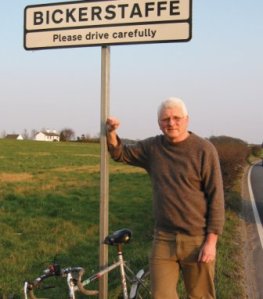

-An argument published from the village and civil parish of Bickerstaffe in the West Lancashire district of Lancashire

“under the censure of lewd customs they include all sorts of public sports, exercises, and recreations, how innocent soever. Nay, the poor rosemary and bays, and Christmas pie is made an abomination.”

-Thomas Lewis, English Presbyterian Eloquence, p. 17, 1720

“Grocers will now begin to advance their plumbs, and bellmen will be very studious concerning their Christmas verses. Fanaticks will begin to preach down superstitious minc’d pyes and abominable plumb porridge.”

-London Bewitched, p. 7, 1708

Sorry for the delay. Stupid technical difficulties. On to the next one!

Keep eating and asking, my friends.

Esther

Bibliography (now in alphabetical order!):

-Ayto, John. “Mincemeat.” An A to Z of Food and Drink. New ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. 213-214. Print.

-Baker, Margaret. “The Christmas Feast.” Discovering Christmas customs and folklore: a guide to seasonal rites. 3rd ed. Princes Risborough: Shire, 1992. 16, 31-33. Print.

-Bowler, G. Q.. “Mince Pies.” The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2000. 147. Print.

-Brand, John, and Henry Ellis. “Yule-Doughs, Mince-Pies, Christmas Pies, and Plum Porridge.” Observations on the popular antiquities of Great Britain: chiefly illustrating the origin of our vulgar and provincial customs, ceremonies, and superstitions, Volume 1. A new ed. London: H.G. Bohn, 1849. 526-530. Print.

-Chambers, Robert. “Old English Christmas Fare.” The Book of days: a miscellany of popular antiquities in connection with the calendar, including anecdote, biography, & history, curiosities of literature and oddities of human life and character, Volume 2. Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers, 1864. 755. Print.

-Cosman, Madeleine Pelner. “Multiple Cookings, Mixings, and Princely Pies.” Fabulous Feasts: Medieval Cookery and Ceremony. New York: G. Braziller, 1976. 60. Print.

-Crump, William D.. “Christmas Pie.” The Christmas Encyclopedia. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2001. 78-79. Print.

-Doerksen, Cliff. “The Real American Pie | Feature | Chicago Reader.” Chicago Reader | Music, movies, news, culture & food. CL Chicago, Inc., 17 Dec. 2009. Web. 13 Dec. 2011. <http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/mince-pie-the-real-american-pie/Content?oid=1267308>.

-Hottes, Alfred Carl. “Mince Pie.” 1001 Christmas Facts and Fancies 1937. New York: A.T. De La Mare Company, Inc., 1937. 184-185. Print.

-John, J.. “Mince pies.” A Christmas Compendium. London: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., 2005. 78-79. Print.

-Lee, N. K. M., and Eliza Leslie. “Pies, mince.” The cook’s own book, and housekeeper’s register: being receipts for cooking of every kind of meat, fish, and fowl and making every sort of soup, gravy, pastry, preserves, and essences : with a complete system of confectionery, tables for marketing, a book. Boston: Munroe & Francis, 1854. 141. Print.

-Miles, Clement A.. “Christmas Feasting and Sacrificial Survivals.” Christmas Customs and Traditions, Their History and Significance. New York: Dover Publications, 1976. 284. Print.

-Muir, Frank. “Chapter VII: Christmas Day – 25 December.” Christmas customs & traditions. New York: Taplinger Pub. Co., 1975. 58-59. Print.

-Olver, Lynne. “The Food Timeline–Christmas food history.” Food Timeline: food history & vintage recipes . Lynne Olver, n.d. Web. 12 Dec. 2011. <http://www.foodtimeline.org/christmasfood.html#mincemeat>.

-Robuchon, Joël. “Mincemeat.” Larousse Gastronomique: The World’s Greatest Culinary Encyclopedia. [Updated] ed. New York: Clarkson Potter Publishers, 2009. 671. Print.

-Stavely, Keith W. F., and Kathleen Fitzgerald. “Apples, Preserves, & Pies.” America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004. 220-228. Print.

Photos, in order of appearance:

-http://www.bbcgoodfood.com/recipes/2174/unbelievably-easy-mince-pies

-http://www.posh24.com/red_carpet/tomkat_awkward_on_the_red_carpet

-http://yummyfoooooood.tumblr.com/post/10290294888/chinese-chicken-balls-and-sweet-sour-sauce

-http://www.essentially-england.com/steak-and-kidney-pudding.html

-http://www.jasonandshawnda.com/foodiebride/archives/1236

-http://allthingsruffnerian.blogspot.com/2010/12/atmores-mince-meat-ad-1870s.html

-http://oneyearandoneth.wordpress.com/

-http://www.flickr.com/photos/hovid/5463949347/

-http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunting

-http://steamykitchen.com/185-saffron-giveaway.html

-http://www.grasslandbeef.com/Detail.bok?no=670

-http://www.godecookery.com/twotarts/twotarts.html

-http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SalemWitchcraftTrial.jpg

-http://www.irishmusicforever.com/irish-history-3

-http://www.thekitchn.com/thekitchn/slinks/look-mini-mince-pies-068505

-http://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/cuisine/christmas-feasts/best-mince-pies-for-christmas-20111205-1oerb.html

-http://missigs.blogspot.com/

-http://mothergoosesmiles.wordpress.com/2011/11/

-http://www.photosofchurches.com/somerset-glastonbury-abbey.htm

-http://www.executedtoday.com/2009/11/15/1539-richard-whiting-abbot-of-glastonbury/

-http://naturewoman.wordpress.com/2007/12/08/none-such-mincemeat/

-http://seedtofeedme.blogspot.com/2011/11/christmas-mince-pies.html

-http://www.cherrapeno.com/2007/12/merry-christmas.html

-http://whateverthingsare.wordpress.com/2007/12/07/recipe-3/

-http://www.bickerstafferecord.org.uk/

-http://www.bestdeal.org/british_store/xkipmp.html

2 thoughts on “Day 12: Mincemeat Pie”