I love gingerbread. I love the cookie kind, the cakey kind, and everything in between. When I went to sleep away camp my favorite dessert was gingerbread cake slopped with whipped cream. It was the best day of the week.

When you think about gingerbread at Christmas, the first thing that probably comes to mind is the flat, crisp cookie that’s made into men whose heads you bite off before destroying their gingerbread homes with your mouth. Of course, there’s still the cake kind, but that’s more of a year round dessert. Both kinds share a common origin that goes way back. And no, gingerbread was not always a Christmas food.

If you want to go real deep, gingerbread actually originates with the ancient Greeks and Egyptians. In 2000 BC, wealthy Greek families would sail to the Isle of Rhodes to buy “spiced honey cakes” and both Greeks and Egyptians used a form of honey cake for ceremonial purposes. Later, the ancient Romans made special, highly spiced honey cakes cooked in a clebanus (a type of portable oven) in their dining rooms. The cakes were taken straight from the clebanus and served directly to guests and visitors. The Romans also made their little honey cakes in the shape of hearts, associating them with weddings. They eventually became edible love tokens, similar to a box of chocolates on Valentine’s Day. Whitman’s Sampler anyone?

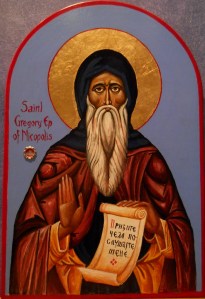

An Armenian monk called Gregory of Nicopolis (Gregory Makar, Grgoire de Nicopolis) supposedly brought honey cakes to Europe in 992. He left Nicopolis Pompeii for Bondaroy, France, where he spent seven years, teaching the art of gingerbread making to the French priests and Christians until he died in 999. At that time, the honey cakes didn’t include any ginger.

The crusaders spread ginger through Europe in the 11th century when they returned from their travels. Ginger, which is native to Malaysia, could be used medicinally for all type of things (flatulence, hangovers, stomach disorders) and quickly became a popular cure. The discovery that ginger could be used a preservative probably lead to the invention of new types of cakes, pastries, and breads, including the gingerbread. The center of the medieval ginger trade was in Nürnberg, Germany, a city that became famous for its gingerbread cakes and cookies, but more on that later.

The term “gingerbread” was not the food’s originally name. In the 13th century, it was called “gingerbras,” the Old French word for “preserved ginger.” Gingerbras meant anything that had been cooked with ginger, and not specifically a cake type item. Gingerbras came from the Latin name for the spice, zingiber. In the middle of the 14th century, -bras was replaced with the more familiar word –bread and by the 15th century, gingerbread had replaced gingerbras altogether.

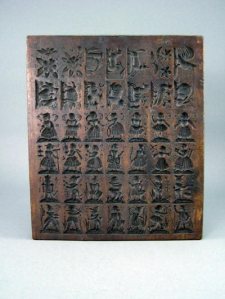

Catholic monks were the first to make honey cakes infused with ginger, and introduced them to Europe in the 1300’s. The monks designed the cakes to be theme “cakes” for Saint’s Days and festivals. The gingerbreads depicted saints and religious motifs, which were imprinted on the gingerbread by molds, called “cookie boards.” They were intricately carved slabs of wood that were pressed into the surface of stiff, rolled dough leaving a detailed image on the surface. Soon, gingerbreads were being made all over Europe, particularly in Germany, Scandinavia, England, and France.

Gingerbread was a favorite uncooked early medieval sweetmeat in England and it was characterized as a “bread stuff,” meaning it was an edible dry finger food eaten to compliment a meal. The spices needed to make it were expensive, so it was only available to those who could afford it. The Duchess of Leicester paid 12 shillings for 4 pounds of loose ginger and another 2 and fourpence for a little less than a pound. That was a high price in 1265. These loose boxes must have been imported from the Netherlands because it paid a small customs duty in London.

Homemade gingerbread was made by mixing breadcrumbs with a paste of honey, pepper, saffron, and cinnamon. A 15th century recipe in Good Cookery called for the breadcrumbs to be boiled in honey with ginger and other spices. It was also common to add sandalwood to color the gingerbread red. The earliest written recipe fails to mention ginger, which could simply be a mistake made by the author. Other gingerbreads were made with mustard, pepper, raisins, nuts, and apples. The breadcrumbs were usually stale and a heavy hand was required with the spices to hide the stale flavor. The bread and honey mixture was pressed into a square loaf so it could be sliced and decorated with gilt. Occasionally it was added to meat dishes to cover the odor of aging meat. Ya know, when it wasn’t exactly fresh.

Ew.

Red gingerbread continued to be popular until the 17th century when it was made with “the grated breadcrumbs of stale manchet [a high quality yeast bread],” flavored with cinnamon, aniseed, and ginger and darkened with licorice and red wine instead of sandalwood. The ingredients were mixed together, rolled thin, and “printed” with cookie boards. Gingerbread wasn’t baked, but placed in a cool oven to dry. White gingerbread was also fashionable, but it was more of a marzipan confection flavored with ginger and also covered with gilt. This is probably where the saying “take the gilt off the gingerbread” (meaning, to remove one’s most attractive qualities) comes from.

Medieval English gingerbread was a treat, but it was also a sort of “medical candy.” Ginger on its own could be used to treat ailments, but so could the tasty “baked” good. It was used as a medicine in other countries as well. Sources show that Swedish nuns from the Vadstena Monastery were using it for digestion problems in 1444. A 16th century writer, John Baret, described gingerbread as “A Kinde of cake or paste made to comfort the stomacke” (Food & Think).

Later in the 17th century, cake baking had become more popular in England and gingerbread changed again. It lost the breadcrumbs and was made with flour, sugar, butter, eggs, and black treacle with ginger, cinnamon, and chopped or preserved fruits for flavor. Sugar was only widely used in sweet foods in the 16th century, so gingerbread began using a little around then. With the introduction of black treacle in England the 17th century, honey used to sweeten gingerbread could be replaced and the amount of sugar used in the recipe could be lessened. It was shaped into cakes and baked in the oven. This continued until the 18th century.

To get the appropriate color, gingerbread had used sandalwood in medieval times and black licorice in Tudor times. Once gingerbread was made with treacle, there was no need to add a coloring agent. Treacle’s already dark color did the job without an extra ingredient. This particular type of gingerbread was a favorite of Charles II. Treacle gingerbread is most closely related to the soft, cakelike type of gingerbread.

There were several types of gingerbread. It could be soft and delicately spiced, crisp and flat, or warm, thick dark squares of cakelike “bread” that was served with a pitcher of lemon sauce or whipped cream. The French made a yeasty spice bread called pain d’epices, with ginger, allspice or cloves, aniseed, and honey. The Italians made panforte, a dense candy-like gingerbread with nuts and dried fruit, shaped into loaves, and baked slowly. Panforte was mainly made commercially rather than at home and was a specialty of Siena. It was said, “during the seasonal baking just before Christmas, one could detect the mouth-watering, spicy fragrance from miles away” (Journal of Antiques and Collectables). The Germans made cookie board stamped gingerbread called lebkuchen and Dutch speculaas cookies were popular in Lowland countries and shaped like every day objects – windmills, farm animals, and farm men and women.

Figure cookie making can be traced back as far as the 16th century in Europe. They were made using intaglio style molds (incised carving) rather than cookie cutters. Queen Elizabeth I enjoyed giving important visitors gingerbread likenesses of themselves cut into slabs of gingerbread using an intaglio cookie mold. Fine ladies at court would sometimes give gingerbread to their favorite knights in tournaments for luck. Gingerbread became so well liked that in 1598, Shakespeare mentioned it in his play Love’s Labour Lost: “An I had but one penny in the world, thou shouldst have it to buy ginger-bread…” (V.i)

With this upswing in popularity, gingerbread was easy to find in England. It was common to run across it at county fairs where it was considered fairground delicacies, and fairs were soon known as “Gingerbread Fairs.” At each fair there was at least one booth where the Gingerbread Woman would sell molded cookies, decorated with bright colors and gilt. The recipe she used probably resembled a medieval one of boiled honey, wine, breadcrumbs, and spices that created a thickened, cooked (not baked) dough. She would shape them into men, women, armor, suns, moons, flowers, birds, or other animals. Gingerbread and other treats bought at fairs were collectively called “fairings.”

(source)

Different cookie shapes were associated with different seasons. Buttons and flowers could be found at Easter fairs and animals and birds at autumn fairs. There was one village tradition in England that required unmarried women to eat gingerbread “husbands” at the fair if they wanted to meet a human husband.

The part they didn’t tell you was if you didn’t eat the gingerbread man, your husband would look like a gingerbread man.

Gingerbread fairs were a huge happening in Germany, where the flat, shaped gingerbread reigned supreme. You can still get shaped gingerbread at modern German autumn fairs, often hearts decorated with colored icing and tied with ribbons. They are usually inscribed with icing messages, for example “Alles was ich brauch bist du” (all I need is you) and “Du bist einfach super” (you’re really super), or simpler ones like “With Love!” and “For Friendship!”

The French also had an annual Christmas gingerbread fair held in Paris. It lasted from the 11th to the 19th century and took place at an abbey that once stood on the site of the present St. Antoine Hospital. The monks cut their gingerbread into the shapes of pigs to reflect the suckling pig that was often a favorite Christmas dish. Gingerbread bakers in Belgium and Holland made huge gingerbread cookies imprinted by cookie boards to put in their windows as Christmas advertising. Several schools of mold carving were practiced there.

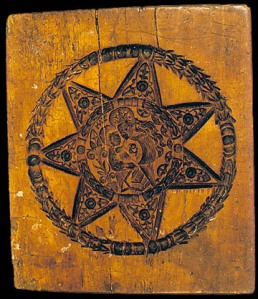

While the shaped gingerbread was fashionable at county fairs, cookie board gingerbread was the mainstay. The boards had become even larger and more extravagantly carved and the images changed in the 17th and 18th centuries because of secularization. They showed pictures of idealized lords and ladies, soldiers, castles, and floral and geometric patterns. There were also images of characters from well-known folktales and legends in Germany. One surviving 17th century cookie board has an image of a sunburst on it to celebrate the winter solstice and lengthening of the day.

Soon after bakers began cutting and decorating the delicious treat, gingerbread making became an actual profession. In 17th century Germany and France, only professional gingerbread bakers were allowed to bake gingerbread. France’s gingerbread guild began in 1571 while Germany’s came into being in 1643 as a means of quality control and to remove competition. At first, this was fine because gingerbread ingredients were costly, but the prices dropped, they were more available to everyday people. Still, these everyday people weren’t permitted to make their own gingerbread, except on Easter and Christmas. The bakers of the German guild were called Lebkuchler.

Nürnberg became known as “the gingerbread capitol of the world” in the 1600’s. Their guild employed master bakers as well as sculptors, painters, woodcarvers, and goldsmiths who all helped make gingerbreads into magnificent works of art. Artists helped decorate gingerbread with frosting, gold paint, or gilt and woodcarvers created beautiful molds to press into the dough. Master bakers used all kinds of spices in their gingerbreads, as many as they could fit, including cardamom, cloves, cinnamon, white pepper, anise, and (of course) ginger. The practice of highly spicing their gingerbread earned the bakers the nickname “pepper sacks.”

Professional gingerbread baking was the job of males, as was carving the cookie boards. All the gingerbreads were made with honey, since there was an abundance of honey hives in forests surrounding Nürnberg. If there were no artisans available, wives and daughters served as decorators to “apply makeup” to the treats.

Professional gingerbread baking was the job of males, as was carving the cookie boards. All the gingerbreads were made with honey, since there was an abundance of honey hives in forests surrounding Nürnberg. If there were no artisans available, wives and daughters served as decorators to “apply makeup” to the treats.

Decorated gingerbreads were often kept as decorations for the home, either on the wall or displayed in glass front cases. The quality of Nürnberg gingerbread was such that it could be used to pay city taxes and was considered a gift worthy of heads of state and royalty. Nürnberg also had the special Christkindlmarkt, a market featuring lebkuchen. The market is continues to be a popular event where you can buy all types of gingerbread, including the traditional imprinted ones. And in case you can’t get to the market, Saint Nicholas, who visits on the evening of December 5th, will be sure to leave you gingerbread as a gift.

Cookie board carving became a popular and respected art. Today, the molds are incredibly expensive and difficult to find, and most known ones are in museums. Some of the best-known areas of mold carving were Lyon, France; Nürnberg, Germany; Ulm, Germany; Toruń, Poland; Pesth, Hungary; and Prague, Czech Republic. The bread museums in Ulm and the Ethnographic Museum in Toruń have two of the largest mold collections in Europe.

Molds were a way to mass-produce designs. Master carvers were available, but as part of their training, gingerbread bakers had to learn to carve molds during their internships and as journeymen. Not all the bakers were great carvers, but they were able to replace molds or create new motifs depending on what was in style. Gingerbread dough was left to sit for two or three months to undergo an enzyme process so it became softer and almost rubbery, but was also dry and hard to handle. Strength was needed to work with the dough, and to properly transfer an image from a mold to the dough, it had to be “beaten out.” This meant the baker literally hit and punched the back of the wooden mold until the image was imprinted on the gingerbread.

Bakers and journeymen made hundreds of cookies in one day. Once the cookies were printed, they were dried at low temperatures in an oven rather than baked in order to keep the image clean and not warp it. A lot of the large surviving molds are from the 19th and 20th centuries:

“One fascinating Dutch board in my collection shows the long life of these cookie forms in Europe. One side is covered with figures in traditional dress, and the other side, apparently carved in a more careless style by another artist at a later period, includes a car, bicycle and a hot air balloon among the more predictable rural references” (Journal of Antiques and Collectables)

There were all kinds of motifs for gingerbread. The classical ones included hearts, babies, and riders. Other motifs had to do with Christmas or Easter. Christmas motifs were usually scenes from the Nativity and the Adoration of the Three Kings, as well as images for the feast of Adam and Eve on December 24th. Bakers also made edible Christmas cards out of gingerbread.

There were all kinds of motifs for gingerbread. The classical ones included hearts, babies, and riders. Other motifs had to do with Christmas or Easter. Christmas motifs were usually scenes from the Nativity and the Adoration of the Three Kings, as well as images for the feast of Adam and Eve on December 24th. Bakers also made edible Christmas cards out of gingerbread.

Imprinted gingerbreads were used for important celebratory events such as weddings. When two noble families were combined, an “allied coat of arms” was carved into a mold and pressed into gingerbread and handed out to all the wedding guests. The bride was presented with gingerbreads with babies on them as a good luck charm. After all, the point of getting married was to have a bunch of kids immediately.

Catholic motifs still included saints but also places of pilgrimage. It was more common to celebrate Name Days rather than birthdays, the day of the saint for whom the person was named. On that day, they were presented with a gingerbread with their patron saint on it. Those going on pilgrimages would carry gingerbreads with a depiction of the place they were visiting on it. This is still practiced today, only now the image is on paper rather than gingerbread. Molds made specifically with children’s images were available and included babies, riders, swords, pistols, trumpets, animals, and at the beginning of the school year, alphabets and school scenes.

Most of the molds were made in the baroque style, because molds were at their finest in the 1600s. However, they wore out so they had to be recopied, meaning that molds made 200 years later still had the same stylistic criteria as the original. The molds served sort of as a history book or newspaper. Images of emperors, empresses, kings, and queens were shown to the public on gingerbread as well as copperplate engravings. There are molds made of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria (Marie Antoinette’s sister who had a baby like immediately) or of Emperor Charles the Great (Ya know, Charlemagne who was actually a lion but was also a shape shifter and could be come a human too.)

I made that up.

I’m not even sure where I got the “lion” part from. Pretty sure I’m confusing several different rulers.

“There were pictures of the giraffe the Egyptian ruler Mehemed Ali gave to the Austrian emperor in 1828 and of the first steamship on the Danube, the Maria Anna, as well as a portrayal of the 1817 European famine that was actually a sociocritical parody of the exorbitant prices of grain. These images represented the big news of the day” (ENotes)

Gingerbread houses came into being in the early 1800’s in Germany, where they were called lebkuchenhäusle. Many claim that they were inspired by the story of Hansel and Gretel and the hexenhäusle (witch’s house) made of bread with a cake roof and barley windows, but there’s no actual proof. The fairytale could actually be based on something that already existed. In any case, after the Grimm brothers published their book in 1812, records of bakers making houses of lebkuchen started popping up. The gingerbread bakers used the same artists and craftsmen who helped them with their regular gingerbread to create elaborate houses to keep in their windows at Christmastime. By the end of the 19th century, Hansel and Gretel and the gingerbread houses had become so popular that the composer Engelbert Humperdink (yes, that’s seriously his name) composed an opera based on the story.

German immigrants, who are now known as the Pennsylvania Dutch, brought the tradition to Pennsylvania. Gingerbread houses were and still are very popular in America, but they were never big in England in the same way.

Speaking of America…

Gingerbread had come to America along with European settlers in colonial times and has been baked here for over 200 years. There were two types of gingerbread in America. There was the honey-based gingerbread with a middle European origin and molasses shortbreads developed in the 17th century from England or Scotland. The soft gingerbread, or “light cakes,” an American adaptation of European gingerbreads, could easily be made by home bakers as a staple dessert, especially when chemical leavenings, such as saleratus, were introduced in the 17th or 18th century. Hard gingerbread was cheap, easy to make, and a small batch would yield plenty of cookies. It cooked well in both brick ovens and cook stoves and was pretty hard to ruin. Pre-Revolution gingerbread took the form of miniature kings, but post-independence, they took on shapes such as eagles.

Americans tended to use fewer spices, but they also used ingredients that were only available locally. For example, maple syrup gingerbread was popular in New England and sorghum molasses was used in the south. The north and Midwest had an influx of northern and middle Europeans, who brought with them Scandinavian cookies like pepparkakor. Today, Midwestern wives will often have “coffee kolaches” (coffee mornings) where they get together, eat Scandinavian style gingerbreads, and drink coffee.

New Englanders had rejected Christmas as a feast celebration in order to reestablish its religious principles. They continued to make gingerbread, imprinting them with molds (Master carver John Conger in New York made especially good carvings), but the association with the Christmas season vanished. Instead, around 1800, gingerbread became associated with New Year’s as a way to continue using them for celebration. Hard gingerbreads, mainly in Pennsylvania with the German immigrants, continued to be associated with Christmas. They were shaped into chubby men or Christmas “memmeli.” They would also cut out and decorate foot high cookies to stand in the windows of their homes, which were often gingerbread men and women iced with rows of buttons and big smiles.

This totally doesn’t fit here, but this is Carl’s house from UP in gingerbread form. Brb, crying because any reference to that movie makes me cry.

In the 19th century, the use of molds began to disappear. Cookie cutters were coming into fashion, which focused more on the form of the cookie rather than on the image on the surface. One of the first forms of cookie cutting was an English method of cutting the dough with a glass or teacup, making ginger biscuits.

In Victorian times, England and America began embracing the German Christmas traditions again, largely in thanks to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Traditions like the Christmas tree, Yule logs, and mistletoe resurfaced. Santa got a makeover when Thomas Nast, a famous 19th century cartoonist, created our modern image of Santa based on the Father Christmas figure of the Lowlands. The tin industry began manufacturing primitive cookie cutters to go along with the rekindling of Christmas and the PA Dutch designed some of the cookie cutter shapes that are still used today.

People began baking shaped gingerbread cookies in mass amounts for decorations, holiday platters, and stockings. Early American cookies were referred to as “cakes.” The cookies were in the form of stars, moons, suns, boy’s and girl’s toys, animals, humans, and the newly evolved Santa Claus. In an 1868 issue of the New York True Democrat, a writer said “Cakes of various forms and quality droop from the different limbs, birds of paradise, humming birds, robins, peewees, and a variety of others seem to twitter among the evergreens” (Journal of Antiques and Collectables). In the late 19th century, images of the commercial Christmas were becoming popular. There were wreaths, stars, Santas, elves, stockings, snowmen, trees, sleds, and Christmas toys. Everyone wanted a cookie cutter that was different from everyone else’s, so they would go directly to tin smiths to request shapes. Gingerbread houses began gracing the windows of bakeries everywhere.

Gingerbread has also been part of American presidential campaigning since the time of Abraham Lincoln:

“All Gingerbread Men Are Created Equal: The folksy childhood anecdote has been a mainstay of presidential campaigning since at least Abraham Lincoln. During a debate, Lincoln told a story about sharing a gingerbread man with a poor neighbor friend, who then remarked, “I don’t s’pose anybody on earth likes gingerbread better’n I do and gets less’n I do.” (http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/food/2011/02/thomas-jeffersons-maple-sugar-love-and-more-presidential-food-facts/)

All over the world today, gingerbread is very clearly connected to Christmas. It can range from the soft, cakey kind to the shaped, crisp kind. Countries still have all their own varieties. In the north of England there is parkin, a gingerbread made with oatmeal and treacle, as well as gingerbread made with treacle or golden syrup and brown sugar; in America, it’s hard and soft gingerbreads made with molasses; in Germany, it’s still lebkuchen, made with honey; in Scandinavia there are pepparkakors, thin brittle biscuits associated with Christmas, that are also used as window decorations; and in Russia, the most famous gingerbreads come from Tula, Vyazma, and Gorodets.

Gingerbread doesn’t have the same popularity in England as it does in Germany and America. Up until the 19th century, gingerbread makers would peddle their wares in the streets of London and could be heard all over the place. By 1951, the tradition had all but disappeared, as noted by the writer Henry Mayhew: “there are only two men in London who make their own gingerbread nuts for sale in the streets.” Gingerbread nuts were round, flat biscuits of gingerbread.

In America, cookie boards have been abandoned in favor of cookie cutters. The closest gingerbread you’ll get to cookie board gingerbread is the Dutch windmill cookies, speculaas. They used to be available in grocery stores, but seem to have slowly disappeared from the shelves.

Commercial Christmas gingerbread really began to blow up in the 1950s when department stores created elaborate Christmas scenes to bring people into the store. The scent of gingerbread was especially effective. One of the most expensive was done in the 1960’s at Famous-Barr, a department store in St. Louis. The store had a full scale Victorian home in the building with the scents of gingerbread wafting from the kitchen. It cost $250,000. Today, companies have taken it one step farther. You can get gingerbread-scented body wash and shampoo, gingerbread scented mascara, and gingerbread scented dog shampoo. Your dog and eyelashes will smell delicious.

Making gingerbread houses with family has become an American Christmas pastime. Premade gingerbread house kits are available nearly everywhere, but all the houses look the same. Way back when, gingerbread houses were all designed by hand, but it took a lot of time and patience and gingerbread is tricky to work with so the practice was abandoned. However, now bakers and artists alike are getting involved in gingerbread house competitions where the point really is to make the most fantastic, hand-cut gingerbread houses around.

No big deal.

And then there’s this guy:

Oh, and I have to show you this as well.

I won’t lie, I love Gingy.

Keep eating and asking, my friends.

Esther

Bibliography:

-Ayto, John. “Gingerbread.” An A to Z of Food and Drink. New ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. 142. Print.

-Bensen, Amanda. “A Brief History of Gingerbread | Food & Think.” Blogs | From Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Media, 24 Dec. 2008. Web. 21 Dec. 2011. <http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/food/2008/12/a-brief-history-of-gingerbread/>.

-Bowler, G. Q.. “Gingerbread.” The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2000. 93. Print.

-Dorfman, Marjorie. “food humor Gingerbread Throughout History.” humor food cooking dining Eat, Drink and Really Be Merry. Eat, Drink and Really Be Merry, n.d. Web. 21 Dec. 2011. <http://www.ingestandimbibe.com/Articles/ginger.html>.

-Fallgatter, Tara. “A Taste of Cyberspace.” WWWiz Magazine. WWWiz Magazine, n.d. Web. 21 Dec. 2011. <http://wwwiz.com/issue04/wiz_d04.html>.

-“Gingerbread History.” Bakersfield Christmas Parade | The Joys of Christmas. Bakersfield Christmas Parade, 5 May 2011. Web. 21 Dec. 2011. <http://bcparade.com/gingerbread-history/>.

-“History of Gingerbread – Ultimate Gingerbread.” Ultimate Gingerbread – Ultimate Gingerbread. Ultimate Gingerbread, n.d. Web. 20 Dec. 2011. <http://www.ultimategingerbread.com/gingerbreadhistory.html>.

-Härandner, Edith. ” Gingerbread – eNotes.com.” eNotes – Literature Study Guides, Lesson Plans, and More.. Gale Cengage, n.d. Web. 21 Dec. 2011. <http://www.enotes.com/gingerbread-reference/gingerbread>.

-Marling, Karal Ann. “Window Shopping.” Merry Christmas!: Celebrating America’s Greatest Holiday. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000. 98. Print.

-Olver, Lynn. “The Food Timeline–Christmas food history.” Food Timeline: food history & vintage recipes . Lynne Olver, n.d. Web. 20 Dec. 2011. <http://www.foodtimeline.org/christmasfood.html#gingerbread>.

-Ross, Alice. ” A Gingerbread Tradition, Hearth to Hearth Article, JOA&C December 2000 Issue.” The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles. A Journal of Antiques and Collectibles, n.d. Web. 20 Dec. 2011. <http://www.journalofantiques.com/hearthdec.htm>.

-“What is the History of Gingerbread?.” wiseGEEK: clear answers for common questions. Conjecture Corporation, n.d. Web. 21 Dec. 2011. <http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-the-history-of-gingerbread.htm>.

-Wilson, C. Anne. “Breads, cakes and pastry; Spices, sweeteners, sausages and puddings.” Food & Drink in Britain: from the Stone Age to the 19th Century. Chicago: Academy Chicago Publishers, 2003. 247, 264, 301, 305. Print.

-http://www.bonappetit.com/recipes/2004/11/old_fashioned_gingerbread_with_molasses_whipped_cream

-http://tastytrix.blogspot.com/2009/12/day-7-medieval-gynger-brede.html

-http://tastebudtravels.blogspot.com/2010/10/food-from-many-greek-kitchens.html

-http://saintsoftheday108.blogspot.com/2010/03/march-16-saint-gregory-makar-bishop-of.html

-http://dailyfitnessmagz.com/2011/01/ginger-nutrition-facts/

-http://www.cookiemold.com/CookieMoldsSPECULAAS.html

-http://www.gingerbreadfun.com/?p=545

-http://www.historicfood.com/Gingerbread%20Recipe.htm

-http://www.flickr.com/photos/baldmonk/682493701/

-http://desserts.wikia.com/wiki/Speculaas

-http://simplyrecipes.com/recipes/gingerbread_man_cookies/

-http://www.mccormick.com/Recipes/Desserts/Gingerbread-Men-Cookies.aspx

-http://www.flickriver.com/photos/neunzehn/4085383059/

-http://blogs.laweekly.com/squidink/2009/12/pain_depices_pigs_nancy_silver.php

-http://www.ckrumlov.info/docs/en/mesto_histor_hicepe.xml

-http://foodlorists.blogspot.com/2008/11/lebkuchen.html

-http://www.galenfrysinger.com/nuremberg_christkindlmarkt.htm

-http://www.visittorun.pl/237,l2.html

-http://cookiemolds.wordpress.com/

-http://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/831039

-http://www.gingerbreadfun.com/?attachment_id=1360

-http://evencleveland.blogspot.com/2010/12/cookie-molds.html

-http://freepages.family.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mcgee411/GHTOUT/Charlemagne-bio.html

-http://operatoonity.com/page/59/

-http://www.momsmustardseeds.com/2011/11/freedom-shift-3-choices-to-reclaim-americas-destiny-and-your-chance-to-win-a-copy/

-http://jovianthunderbolt.blogspot.com/2010_12_01_archive.html

-http://www.familylifeinlv.com/2011/01/swedish-cookie-monster.html

-http://www.craftster.org/forum/index.php?topic=332999.0

-http://backyardneighbor.typepad.com/backyard_neighbor/2011/12/vintage-thingy-thursday-cookie-cutters-for-cookie-day.html

-http://cleveland.about.com/od/winterholidayevents/ig/CBG-Gingerbread-Houses/CBG-Gingerbread—Ivy-Mansion.htm

-http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/cookbooks/display.cfm?TitleNo=13&PageNum=407

-http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/26176/structural-gingerbread-gingerbread-house

-http://www.kitchenist.com/cooking/sweet/cookies-for-the-cold-red-hot-gingernuts/1940

-http://www.houstonpress.com/slideshow/the-3rd-annual-christmas-tail-gingerbread-dog-house-competition-at-voice-31959286/

-http://artisancakecompany.com/2010/11/amazing-gingerbread-houses/

This is a terrific post — lots of research, well written, and great photos. Thanks!

Glad you liked it! Thanks for reading.

Esther

Magnifique, wonderful! I learned so much. Can you tell me perhaps which ingredients or how they did their “gilt”? Gold?

Thank you again,

Pascale

Hi Pascale,

Unfortunately I’m not sure how it’s done. I would have to do a little more research and right now I’m so swamped (grad school + work = hair pulling) that I might not have the time! I’ve taken note of your question and will get back to you!

Thanks for reading!

Esther