I guess the most important thing about having an interest in food and food writing is the willingness to try new things. Take a shot at something you normally would gag at the thought of. It seems that in that area, I lack. Example: Scrapple. I would not eat it. I outright refused with very little basis for said refusal.

I think it had more to do with the name than anything else. The word “scrap “ is in it. It immediately conjures images of the parts of the pig no one would ever eat and this…this “scrapple” is how they (whoever “they” are) tricked you into eating those scraps. By making it look like a delicious piece of fried crispy stuff. The way your mom did with broccoli by putting cheese all over it.

Oh my gawsh. Was I ever wrong, or what?

As you’ll remember from this, I am a convert. But in my defense, scrapple’s origins seem pretty nasty. That is, according to our American eating style.

I’m going to start at the beginning. The scrapple we know, Philadelphia scrapple, did not originate here in America. The origins of the food can be traced back to the Middle Ages in Europe. In fact, according to Williams Woys Weaver, it springs from the idea of the ritual slaughter in ancient European times.

There are two specific Celtic feasts which may have helped bring about our modern scrapple: one was Lughnasa, a feast in honor of the god Lugh or Lugus in August, which has a direct link to the swine god Moccus (interesting side note: the name “Moccus” is where the word for what pigs wallow in comes from – muck). It was the time of year when pigs were butchered to make bacon, ham, and sausages in preparation for the coming fall and winter.

The other festival was Samain, the Celtic New Year on November 1st, celebrating underworld, death, and renewal. Depictions of wild boar (the highest ranked pig) tending to the Celtic god of the underworld, Cernunnos, have been uncovered in a Neolithic site at Durrington Walls in England. Both of these feasts revolved around the ritual slaughter of pigs.

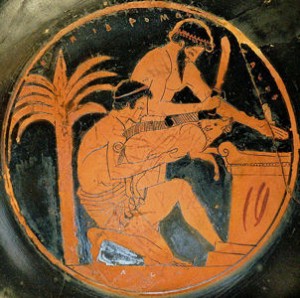

(This picture below comes from a symbol dictionary. Read it. Pretty nifty.)

The association of pigs with the underworld is also present in Greek mythology. A swineherd by the name of Eubouleos witnessed Persephone being taken into the underworld by Hades. When other Greeks heard of this, they gave him the position of priest of the Mysteries of Demeter at Eleusis in Attika. Since it was said that his pigs fell into the hole where Persephone disappeared, swine were the most common sacrifice during rituals for Persephone and Demeter.

In any case, slaughtering pigs became a symbol of fall butchering and preparation for winter throughout the Middle Ages. During the fall butchering done by the Gaul’s, meat was divided according to social hierarchy. The rich guys got the meatiest, fattiest stuff, and the poor guys got a meat-flavored gruel. The villagers who helped with the butchering, however, were rewarded with sausages or meat, as well as a bowl of butcher’s stew*. What is butcher’s stew? The remains of the butchering process thickened with meal. When it was allowed to sit and thicken, it set like a pudding. It was the original scrapple.

*Judging by pictures I’ve found now, butcher’s stew has changed a lot. It now includes large chunks of meat as well as vegetables and a thick, gravy like sauce. Basically, it’s become beef stew. Or, it’s a Pedigree dog food flavor.

This tradition persisted all over Europe, however the recipe changed depending on the type of grain that was available. This would slightly alter the taste and texture of the dish, but the idea was the same. People would either boil it with meal or flour, or bake it, which resulted (respectively) in two types of scrapple: the scrapple we know today or the meat pates associated with French cuisine.

The composition of scrapple also has a special significance, especially in early Celtic culture. Scrapple then (and now) is made using a broth, usually a pork stock. During the boiling process, the broth would turn white by bones and leftover bits of meat. There are two names for this white broth: bouillon-blanc (which is French for white stock) or mullein. Mullein comes from the name of an herb, orange mullein that was sometimes used to flavor the stock. In fact, if you even Google “boullion-blanc” you end up with pictures of orange mullein.

The ancient Celts believed that by drinking this stock the consumer would take on qualities of the pig, such as sexual potency, badass fighting abilities, and fertility. The orange mullein was thought to possess magic and medicinal qualities, but served mainly as a digestive aide. And after a big meal of meat and fat, you’d need it. There was also a psychological significance to the color. The most potent things were white: semen (giving life), milk (sustaining life), and mistletoe berries (poisoning the life out of you).

Likewise, the blood used in the scrapple held a special significance. They were a little more literal with this one. Blood is the life-force of the creature that it is taken from. Therefore, the eater is ingesting another’s life-force and adding to their strength and vitality. Using blood in this way made early scrapple similar to blood puddings and sausages.

So, to recap: scrapple comes from the long tradition of the fall harvest and ritual sacrifice, white broth means you can get ladies pregnant and also kill people, and the blood means you’re strength is greater than others.

I bet you hate me a little for breaking it down into one sentence after seven paragraphs. But believe me, I’m not done.

Stay tuned for the next section: scrapple during the Middle Ages and its move to America.

Keep eating and asking, my friends.

Esther

Esther Great Post! Love the photos and all the information!

Who knew Scrapples history was so interesting! It certainly goes back much further then I would have ever guessed. Thanks!

Wow! Beautiful article! Thank you!